Attachment is the emotional connection formed between an infant and their primary caregiver, impacting the child’s comfort-seeking behavior when distressed. Attachment Theory, introduced by John Bowlby and expanded through Mary Ainsworth’s research, suggests that early attachments shape one’s self-perception, relationships, and behavior into adulthood.

Ainsworth identified three initial attachment styles, secure, ambivalent, and avoidant, later expanded with the disorganized style by Main and Solomon. These styles, evident in childhood, influence adult relationship patterns. Understanding and addressing one’s attachment style can foster healthier relationships and personal growth.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What is attachment?

- What is Attachment Theory?

- What are attachment styles?

- What are the types of attachment styles in children?

- What are the types of attachment styles in adults?

- How are attachment styles formed?

- How are attachment styles assessed?

- What are attachment issues?

- How to have a secure attachment style in adulthood?

- What is Attachment Parenting?

- How does a parent’s attachment style affect their parenting?

- References

What is attachment?

Attachment in psychology is the emotional bond developed between an infant and the primary caretaker during the early years. Attachment is also the tendency of young children to seek comfort from the caregiver when frightened, worried, vulnerable, or distressed.1

What is Attachment Theory?

Attachment Theory is a psychological theory and framework for understanding the importance of these early attachments in child development. The theory suggests that attachment is formed so that the child can remain close to the attachment figure. This proximity-seeking behavior is believed to arise through natural selection in evolution to maximize survival.

According to this theory, early attachment experiences shape how children view themselves, others, and their relationships. If a child feels safe and supported, they use the attachment figure as a secure base to confidently explore the world. Whether a child forms a secure attachment will affect their development, perception of the world, and future relationships.2

Who developed the Attachment Theory?

The Attachment Theory was proposed by British psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby after studying the negative impact of maternal deprivation on young children. The first formal proposal of this theory was presented to the British Psychoanalytic Society in London in three papers: “The Nature of the Child’s Tie to His Mother” (1958), “Separation Anxiety” (1959), and “Grief and Mourning in Infancy and Early Childhood” (1960).

Mary Ainsworth conducted her landmark Baltimore Longitudinal Study in Ganda, Uganda, while working under Bowlby. She observed distinct patterns in mother-child interactions, leading her to categorize attachment into three types: secure, insecure, and not-yet attached. The insecure style was later divided into ambivalent and avoidant styles. Later, researchers Main and Solomon added the disorganized attachment style as the fourth type in 1986, resulting in three insecure attachment styles.3

Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver extrapolated the Attachment Theory in 1987, applying it to close relationships in adults and replacing the caregiver with the romantic partner as the attachment figure. Researchers noted that adult attachment models continue to guide and shape romantic relationship behavior throughout life. Hazan and Shaver proposed three adult attachment styles: secure, anxious-ambivalent, and avoidant.

A fourth attachment style was proposed by Kim Bartholomew in 1990 since there were two distinct forms of avoidant individuals. The resulting four-category attachment model is commonly used in research today.4

What is the Bowlby-Ainsworth Attachment Theory?

The Bowlby-Ainworth Attachment Theory was named after John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth because they were the pioneers who jointly developed this theory. Many developmental psychologists and scientists continued to conduct studies on this topic and expanded the theory.5

Why is the Attachment Theory important?

The Attachment Theory and related research contribute to understanding how parenting style affects a child’s personality development, future relationships, and outcomes in life.

Before the emergence of this theory, the prevailing psychoanalytic theory led by Freud held that a child developed a tie to their caregiver for feeding and dependency. The child’s feeding needs were the main factors shaping their attachment development. However, this behaviorism theory did not explain why a child would develop anxiety about becoming separated from their parents.

Bowlby’s attachment research proved that the parent-child bonds, not the feeding needs, were vital in forming secure attachments in children. Attachment styles are based on relationships, not on feeding alone. Bowlby’s findings demonstrated pervasive ill effects of institutional and hospital care on children, which behaviorism theorists could not explain.6

What are attachment styles?

In children, attachment styles are the patterns of behavior infants develop to stay close to or draw attention from their caretakers. Different patterns of behavior develop based on the responsiveness of the caretakers.

In adults, attachment styles are the patterns of behavior they exhibit in close relationships when interacting with their romantic partners.

What are the categories of attachment styles?

There are two categories of attachment styles – secure and insecure.

A secure attachment forms when the primary caregiver is responsive to a child when they are in distress.

An insecure attachment forms when the primary caregiver is not responsive to a child when they are in need. The caregiver may ignore, reject, or cause fear in the child rather than provide them with comfort and security.

What are the types of attachment styles in children?

There are 4 types of attachment styles in children. Here is the list of attachment styles in children.

- Secure attachment

- Ambivalent attachment

- Avoidant attachment

- Disorganized attachment

Besides the secure attachment style, the remaining three attachment styles are insecure.

In children, the sensitivity and responsiveness of the parent or primary caregiver cause children to form different attachment styles.

Secure attachment in children

A secure attachment is a healthy emotional bond in a child when their primary caretaker, usually a parent, is consistently sensitive and responsive to the child’s needs.

A securely attached child is comfortable relying on their parent to help regulate their emotions. They become visibly upset under distress, such as the parents leaving the room. When the caregivers return after a short departure, children are happy and easily comforted.

Secure children often develop strong self-esteem and healthy emotional regulation skills. They are comfortable expressing emotions and competent in social interactions. In a secure attachment, a child confidently explores the world, relying on their parent as a secure base.

Ambivalent attachment in children

An ambivalent attachment is an insecure attachment bond that develops in a child when their parent is inconsistent, preoccupied, or unresponsive to the child’s needs.

An ambivalently attached child shows anxiety and uncertainty in relying on their parent for emotional regulation. They exhibit intense distress when separated from their caregivers and may not be easily comforted upon their return, often showing clinginess or resistance.

Children with ambivalent attachment may struggle with low self-esteem and difficulties in emotional regulation. They are hesitant in expressing emotions and may face challenges in social interactions. These children display caution in exploring the world, exhibiting a lack of confidence in their parents as a secure base.

Avoidant attachment in children

An avoidant attachment is an insecure attachment bond that develops in a child when their parent is rejecting or punitive when the child is distressed.

An avoidant child does not trust that they can count on their caretaker for help or comfort when needed. They appear indifferent to their parent’s presence, showing little distress when the parent leaves and avoiding contact upon their return. They learn to self-regulate their emotions, often suppressing their feelings of distress or need for comfort.

Children with an avoidant attachment may develop a sense of independence that masks underlying emotional unavailability and difficulties in trusting others. They are reticent in expressing their emotions and may struggle with social relationships. These children often explore the world with an apparent self-reliance, maintaining a distance from their parents rather than using them as a secure base.

Disorganized attachment in children

A disorganized attachment is an insecure attachment that forms in a child when the parent is someone the child fears, often due to child abuse or maltreatment. When the caregiver is a source of both comfort and fear, the child experiences confusion and fear.

A disorganized child shows inconsistent and erratic behaviors towards their caregiver, showing a mixture of approach and avoidance without a coherent strategy for getting their needs met. They may display frozen postures, dazed expressions, or sudden movements under stress or upon the caregiver’s return.

Children with disorganization struggle with emotional regulation, often displaying heightened fear or disorientation even in non-threatening situations. These children face significant challenges in developing self-esteem, trust in others, and healthy emotional expression. They are cautious and confused in social interactions. They may find it difficult to explore the world confidently, lacking a secure base in their caregivers to return to for comfort and safety.

What are the types of attachment styles in adults?

Adult attachment styles are associated with a person’s attachment history. Both early life attachment experiences and previous close relationships can influence attachment styles in adults.

There are 4 attachment styles in adults parallel to the child attachment styles.7

- Secure attachment: Secure attachment in adults is a healthy emotional bond formed in an intimate relationship. A secure attachment style often results from consistent caregiving experienced in childhood or close relationships in adulthood. Securely attached individuals are comfortable with intimacy, able to seek and provide support when needed, and capable of managing their emotions effectively. They have a healthy sense of worthiness and trust that others will be supportive and reliable. Secure adults tend to form long-term interpersonal relationships that are healthy and adaptive.

- Anxious attachment: Anxious attachment in adults is an insecure emotional bond formed in intimate relationships. An anxious attachment style tends to be caused by inconsistent caregiving experienced in childhood or previous adult relationships. Anxiously attached adults crave closeness and intimacy yet fear abandonment and rejection. are highly sensitive to their partners’ responses and may seek excessive reassurance and support, finding it difficult to manage their emotions independently. They harbor a deep-seated fear that they are not worthy of love and have a pervasive worry that others will not be available or responsive to their needs. Adults with anxious attachment tend to experience intense and volatile interpersonal relationships characterized by a constant search for security and acceptance.

- Avoidant attachment: Avoidant attachment in adults is a form of insecure emotional bonding in intimate relationships. This attachment style usually arises from a history of caregivers who were rejecting, causing them to value independence and self-sufficiency over intimacy. Avoidantly attached individuals often maintain a distance from their partners, resisting closeness and emotional vulnerability due to a deep-seated fear of dependency and a belief that showing needs will lead to rejection. They manage their emotions through withdrawal and self-reliance, doubting the availability and supportiveness of others. Adults with avoidant attachment tend to engage in short-term relationships or exhibit a pattern of emotional detachment in longer relationships, struggling to form deep, meaningful connections.

- Fearful attachment: Fearful attachment in adults is a complex form of insecure emotional bonding characterized by a push-pull dynamic in intimate relationships. This style originates from a background of inconsistent or traumatic caregiving. Adults with fearful attachments deeply crave emotional closeness yet are intensely afraid of being hurt or abandoned. These individuals oscillate between desiring intimacy and fearing the vulnerability that comes with it, leading to behaviors that both seek and resist closeness. They are plagued by mistrust and anxiety about their worthiness of love, coupled with a strong fear that others will not be genuinely supportive or will ultimately cause them harm. Fearful people often experience tumultuous relationships, marked by high emotional turmoil and difficulty maintaining stable, trusting connections. This attachment style reflects a profound conflict between the need for attachment and the fear of intimacy.

How are attachment styles formed?

Attachment styles form through the complex interplay between the caregiver and the child. Here are the factors influencing the type of attachment styles formed.

- Responsiveness: A parent who practices responsive parenting and is sensitive to their child’s needs lays the foundation for secure attachment.

- Consistency: A predictable parent who responds to the child reliably creates confidence in the child.

- Emotional availability: An emotionally available parent attuned to the child’s distress signals helps the child develop emotional regulation.

- Temperament: A child’s innate temperament influences their reactions to experiences.

- Reciprocal influence: A flexible parent can adapt to the child’s unique needs, regardless of the child’s easy or challenging temperament.

- Trauma: Severe disruptions, such as abuse, or neglect can affect a child’s ability to trust and form healthy bonds.

- Stressors: Financial hardship, marital discord, or serious illness can disrupt the parent’s availability and responsiveness.

- Parent’s attachment history: A parent with insecure attachment may be preoccupied with their own attachment issues and not available to meet their child’s needs.

- Culture: How a culture values emotional expression or parenting practice can shape a parent’s responsiveness.

How are attachment styles assessed?

In children, the attachment styles are assessed in the Strange Situation.

In adults, many methods have been created over the years to assess attachment styles. The two more well-known methods are the Adult Attachment Interview and the four-category model of adult attachment.8

What is a Strange Situation?

The Strange Situation was initially developed by Mary Ainsworth in 1969 to observe children’s interactions and exploratory behaviors under low and high-stress conditions.

The experiment consists of structured observation, lasting about 20 minutes and involving eight segments. It begins with a mother and her infant entering a specially designed-laboratory playroom. After they settle in, an unfamiliar woman joins them. The scenario unfolds with the mother leaving the room briefly, allowing the stranger to interact with the infant. The mother returns, followed by another separation where the infant is left alone. The experiment concludes with the stranger and then the mother re-entering the room.

Ainsworth discovered unexpected patterns of infant reunion behaviors, which led to the development of a classification system for analyzing attachment styles in children. This observational procedure became the most prevalent method to identify attachment styles in children between 10 and 30 months.

What is an adult attachment interview (AAI)?

The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), developed by George, Kapan, and Main in 1984, evaluates how individuals reflect on and discuss their childhood experiences. The interview, conducted by interviewers with in-depth training, focuses on the coherence of the individual’s narrative.9

What is the four-category model of adult attachment?

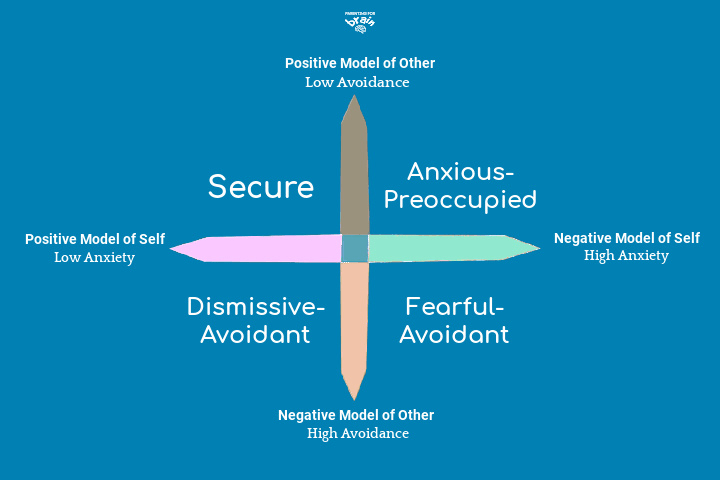

The four-category model of adult attachment was created by Bartholomew using a mix of history interviews and self-reporting. The attachment is determined by a two-dimensional model representing the model of self and the model of others.

Early life interactions with caregivers form an internal working model that shapes a person’s view of themselves and others.

The model of self is the degree to which an individual has internalized the concept of self-worth and the likelihood of feeling anxious in romantic relationships. The self-model is associated with the degree of attachment anxiety and dependency experienced in close relationships.

The model of others measures how often people expect others to be available and supportive and whether these people favor or avoid close relationships. The other model is linked to the degree of avoidance of others.10

What is an internal working model?

An internal working model (IWM) is a representation formed based on interactions with primary caregivers. This model shapes a child’s world views and sets the expectations of interacting with others. These unconscious beliefs and expectations influence how people perceive and respond to others and situations.

A person’s internal working model guides whether they approach relationships with openness or suspicion. The model also affects a person’s security. An insecure IWM is linked to an increased risk of mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression.

What are attachment issues?

Attachment issues refer to difficulties forming and maintaining healthy emotional bonds with others, often rooted in early childhood experiences interacting with the parent or primary caregiver. This term is not a formal medical diagnosis.

Although the term “attachment issues” is often used in the context of adult attachments, children can also have attachment issues. In children, attachment issues are typically described by the type of insecure attachment.

Can attachment styles change?

Yes, a person’s attachment style can change due to neuroplasticity, which means our brains are constantly adapting. With new life experiences, our brains can change and form new neural pathways. Therefore, the attachment patterns laid down in childhood aren’t set in stone.

How to have a secure attachment style in adulthood?

New life experiences in adulthood can help you develop an earned secure attachment with a surrogate attachment figure.11,12

- Commit to making changes: A 2019 study published in the Journal of Marital and Family Therapy showed that those who succeeded in earning a secure attachment were intentional about changes. Deliberate efforts, initiative, and diligence can lead to growth and success.

- Develop secure relationships: Healthy relationships with partners, friends, or therapists who are sensitive and responsive to your emotional experiences can gradually provide a “corrective” experience. These people act as surrogate attachment figures, helping you build trust and reshape your internal working model.

- Overcome setbacks: The 2019 study highlights that overcoming insecurity involves patience and a readiness to navigate difficulties and setbacks in new relationships.

- Avoid and leave unhealthy relationships: Recognize patterns that don’t serve your well-being, assert boundaries, and decide to step away from relationships that perpetuate insecurity. Seek help to leave an abusive relationship if needed.

- Have self-compassion: A 2016 study by Grove City College revealed that having self-acceptance with an attitude of kindness toward the self was correlated with earning a security attachment in adulthood.

- Practice mindfulness: Use mindfulness, such as meditation or yoga, to enhance self-awareness to consciously respond to situations rather than reacting out of emotions.

- Be patient: Know that changing your attachment style is not a switch but a gradual process. Don’t give up, and keep working to achieve your goal.

What is Attachment Parenting?

Attachment Parenting (AP) is a term William Sears popularized in a 1993 book titled The Baby Book. The concept of parenting to foster a secure attachment dates back to 1960-1980s when Bowlby and Ainsworth developed the Attachment Theory.

At the heart of AP, parents learn to read the baby’s cues and respond appropriately to those cues. It is a child-centered approach to parenting. Parent’s responsiveness has been proven to be associated with secure attachment development. The AP method is, therefore, believed to result in attachment security.

However, research supporting the benefits of responsive parenting often lacks clarity on what constitutes responsiveness. The impact of AP-recommended practices like co-sleeping and breastfeeding on fostering secure attachment hasn’t been thoroughly studied.

How does a parent’s attachment style affect their parenting?

Secure attachment in parents is associated with authoritative parenting, while fearful attachment is linked to permissive parenting, according to a 2015 study by Bucharest University.13

Another study published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin in 2013 found an association between anxious and avoidant attachments with authoritarian and permissive parenting styles.14

How can a parent overcome an insecure attachment with their infant?

To overcome an insecure attachment with their infant, a parent can change their parenting style and how they interact with their infant. Responding consistently to the child with attunement and empathy and attending to their needs can help them develop a secure attachment.

If the parent also has an insecure attachment style, they can work on understanding their childhood, change their parenting styles, and become more responsive to their child.

References

- 1.Ainsworth MD. Patterns of attachment. The Clinical Psychologist. 1985;38(2):27–29.

- 2.Fearon RMP, Roisman GI. Attachment theory: progress and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology. Published online June 2017:131-136. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.002

- 3.Main M, Solomon J. Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In: Affective Development in Infancy. Ablex Publishing; 1986:95–124.

- 4.Bartholomew K. Avoidance of Intimacy: An Attachment Perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. Published online May 1990:147-178. doi:10.1177/0265407590072001

- 5.Bretherton lnge. The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. A century of developmental psychology. Published online 1994:431-471. doi:10.1037/10155-029

- 6.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. Published online October 1982:664-678. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

- 7.Feeney JA, Noller P. Attachment style as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Published online February 1990:281-291. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.2.281

- 8.Feeney JA, Noller P, Hanrahan M. Assessing adult attachment. In: Attachment in Adults: Clinical and Developmental Perspectives. Guilford Press; 1994:128–152.

- 9.van IJzendoorn MH. Adult attachment representations, parental responsiveness, and infant attachment: A meta-analysis on the predictive validity of the Adult Attachment Interview. Psychological Bulletin. Published online May 1995:387-403. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.387

- 10.Griffin DW, Bartholomew K. Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Published online September 1994:430-445. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.430

- 11.Dansby Olufowote RA, Fife ST, Schleiden C, Whiting JB. How Can I Become More Secure?: A Grounded Theory of Earning Secure Attachment. J Marital Family Therapy. Published online October 2019:489-506. doi:10.1111/jmft.12409

- 12.Homan KJ. Secure attachment and eudaimonic well-being in late adulthood: The mediating role of self-compassion. Aging & Mental Health. Published online November 16, 2016:363-370. doi:10.1080/13607863.2016.1254597

- 13.Doinita NE, Maria ND. Attachment and Parenting Styles. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. Published online August 2015:199-204. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.282

- 14.Millings A, Walsh J, Hepper E, O’Brien M. Good Partner, Good Parent. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. Published online December 6, 2012:170-180. doi:10.1177/0146167212468333