- What is emotional regulation

- How does emotional regulation in children develop

- How to help a child regulate their emotions

- Is your child having tantrum problems

Emotional regulation is not a skill we are born with.

Toddlers’ moods can swing like a pendulum.

Helping our kids self-regulate a wide range of emotions is among parents’ most important tasks.

This article will examine how emotional self-regulation develops and how we can help children acquire this crucial skill.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

What is Emotional Regulation

Emotional regulation or self-regulation is the ability to monitor and modulate which emotions one has when you have them and how you experience and express them.

Learning to self-regulate is a key milestone in child development – whose foundations are laid in the earliest years of life.

A child’s capacity to regulate their emotional state and reactions affects their family, peers, academic performance, long-term mental health, and ability to thrive in a complex world.

Relationships with Family and Peers

A child with poor emotion regulation skills throws tantrums constantly and strains the parent-child relationship.

This can impact the climate of the whole household, including siblings or everyone around them, and lead to a negative spiral.

Similarly, for friendships, kids who can’t control their big feelings have fewer social skills.

They have a more challenging time making or keeping friends.

The inability to self-regulate big emotions can lead to traits like anger, withdrawal, anxiety, or aggressive behavior.

All this can snowball into further negative consequences: Children who their peers reject are at increased risk of dropping out of school, delinquency, substance abuse, and antisocial behavior problems.1

Those who are withdrawn and rejected by peers are also more likely to get bullied.2

Performance and Success

In contrast, good emotional regulation in children not only positively impacts relationships but is also a strong predictor of academic achievement and success.3

Effective emotion management allows students to focus on performing during tests and exams rather than being impaired by anxiety.

Students who can self-regulate also have better attention and problem-solving capabilities and perform better on tasks involving delayed gratification, inhibition, and long-term goals.

This effect carries on throughout life.

An adult who cannot master emotional regulation enjoys less job satisfaction, mental health, or general well-being.4

Resilience and Mental Health

Meanwhile, kids who have learned to regulate their emotions can also better handle and bounce back from trauma or adverse events: They have a higher frustration tolerance and more resilience.

Many clinical disorders in children are closely related to emotional regulation or, rather, the lack of it.

For example, emotional dysregulation in children is linked to behavioral disorders like Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and it can put a child at significant risk of developing emotional disorders such as anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and clinical depression.

The child is also more susceptible to developing future psychopathology.5

Given all this, it’s unsurprising that experts consider emotion regulation or self-regulation skills essential for children to develop.

Watch this video from The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University.

How Does Emotional Regulation in Children Develop

So, how do kids develop these critically essential skills? And how can we, as parents, help them?

To answer these questions, let’s examine what emotional regulation for kids means.

Note: To self-regulate, we need to notice, monitor, and recognize different feelings – and adapt them appropriately for each situation.

This doesn’t always mean decreasing negative feelings and increasing positive ones. Merely suppressing negative feelings and forcing ourselves not to express them is not a good self-regulation process.

Is It Easier for Some Children To Learn Emotional Regulation Than Others?

If it seems some kids have a tougher time learning emotional regulation skills, while it comes naturally to others, you’re not imagining things.

Researchers have found that some babies’ temperament is innately more capable of self-regulating than others.6

But while genetics matter, a child’s environment is just as important, if not more.

The capacity to self-regulate is not set in stone: All children can learn to manage their feelings, given an appropriate environment.

A study in a Romanian orphanage illustrates the importance of the environment.

In the study, some orphans were randomly assigned to foster homes with high-quality care, while others stayed in the orphanage.

The adopted children significantly improved emotional regulation over those who stayed.7

Also See: How Co-regulation Develops into Self-Regulation in Children

Why Childhood Life Experiences Matter In Learning Self-Regulation Skills

When babies are born, their brains are not yet well developed.

We can think of their brains developing like building a house.

The architectural blueprint may give a house its shape, but the outcome will vary significantly if made of straw, wood, or brick.

Similarly, genetics determine the base blueprint for a child’s brain development, but their life experiences, like the house’s construction materials, can profoundly influence the outcome.8,9

And just as it’s easier to impact the house during the building phase than to alter it later, so can human brains acquire some skills better or more easily during specific periods in life.

These optimal times are called sensitive periods or critical periods.

After the sensitive period of learning a skill has passed, there is a gradual decline in the ability to become proficient.

It is still possible to acquire a new skill, but it will take longer, or the person will be less likely to get good at it.

For instance, studies show that the sensitive period to learn a second language and become genuinely bilingual is generally before puberty.10

In the Romanian orphanage experiment, orphans who foster families adopted before age two developed emotional regulation skills comparable to children who were never institutionalized.

Therefore, the sensitive period of emotional self-regulation is believed to be before children ages two.

As proven by science, the importance of early childhood life experiences cannot be overstated.

However, this doesn’t mean that once kids pass that age, they’ve missed the opportunity to learn self-regulation.

It only means it will be more challenging and take more time and patience.

So it is better to do it right the first time when kids are young than to fix it later.

If your child is older, don’t despair. It’s never too late to start helping children learn to self-regulate.

What you need is to start now – the sooner, the better.

On the other hand, it also doesn’t mean the process of learning to self-regulate is over by age two – far from it.

A child’s brain doesn’t finish developing until the mid-twenties.

Parents’ Role in Helping Children Acquire Emotion Regulation Skills

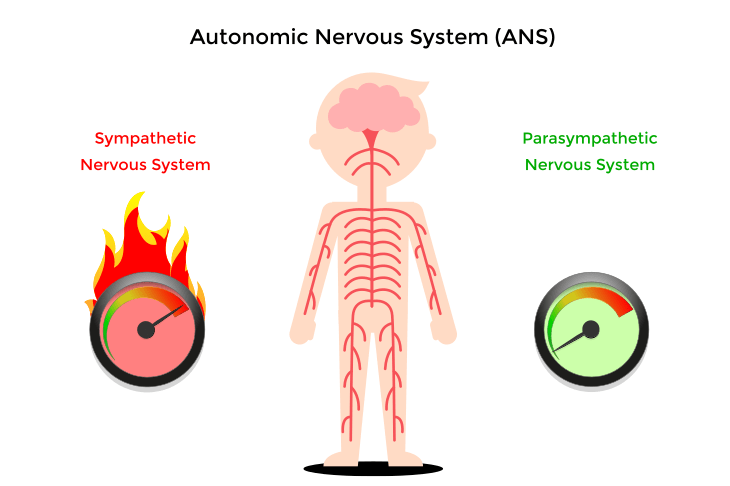

Our brains regulate through two parts of our nervous systems.

First, there’s an emergency or quick-response system – the “gas pedal.”

Its primary job is to activate the body’s fight-or-flight response.

Think of this as the gas pedal in a car.

When activated, this system allows our bodies to move fast by speeding up our heart rate, shutting down digestion, and upping blood sugar for quick energy.

When a baby or child gets worked up, this system is in full gear, and the emotions are at “high speed.”

Sometimes, this reaction is referred to as the emotional brain (or downstairs brain) taking control.

Second, there is a calming or dampening part of the brain – the “brake.”

This system is slower to activate, but when it does, it slows down our heart rate, increases digestion, and conserves energy.

The infant’s ability to regulate emotions is tied to the maturation of their braking system.

This calming part of our nervous system can counter the “high speed” effect created by the fight-or-flight system, and it’s crucial in controlling our bodily functions and emotional well-being.

This calming system is regulated by the cognitive brain (or upstairs brain).

When these systems are acting in balance, our bodies run properly, and we are in emotional control.

But when the systems are out of balance, we must draw on our self-regulation techniques to return them to a healthy state.

Since the fight-or-flight response is critical for human survival, it is no coincidence that the “gas pedal” develops before birth.

Every parent knows newborns can get worked up enough to alert parents to their needs or perceived danger through crying.

However, the “brakes” system is not as well developed at birth.

Infants have limited self-regulation capabilities, such as thumb sucking, visual avoidance, and withdrawal.

But they can only self-soothe to a certain point, especially if they’re highly worked up or if whatever upset them doesn’t stop.

To make things worse, the “gas pedal” can trigger the release of a stress hormone to suppress the “brake.”

Babies crying uncontrollably are driving an emotional runaway car with no brakes! It is up to us, the parents, to help them regulate their emotions.

Their nervous systems are not yet up to the task alone.

Also See: Bottling Up Emotions

How to Help a Child Regulate Their Emotions

While many factors, including teachers, schools, neighborhoods, peers, culture, and genetics, can influence a child’s ability to regulate, parents and family play a central role.

Let’s look at the following main factors that influence children’s ability to self-regulate their emotions.

1. Parents Modeling Emotion Regulating Skills

Modeling has long been recognized as a crucial mechanism through which children learn.

Kids observe their parents’ every move, internalizing and mimicking their behaviors.

Their parents’ ability to practice self-regulation is among the first emotion-related modeling children see.

Kids learn the “correct” reaction in different situations.

They watch how parents control and struggle with intense emotions and impulses.11

Research shows that children of parents who struggle with emotional regulation are more likely to have dysregulation.12

If a parent is reactive, screams, or yells whenever something goes wrong, the child learns to be reactive and misbehave when things don’t go their way.

If a parent is calm and thinks critically to solve problems, the child is more likely to stay calm and look for solutions instead of blame.

The younger the child, the stronger this imitation effect.13

Besides active observation, children also learn through emotional contagion – when kids unconsciously sense their parents’ emotions and respond with similar feelings.14

For example, when parents frown, raise their voices, or make angry gestures, kids become angry, too.

When parents raise their voices, kids also increase their volume.

Parental modeling is the number one way to teach children self-regulation.

Emotional regulation in children comes from emotional regulation in the parents.

Emotion regulation activities or tools geared towards children should only be used as a supplement or last resort for kids who don’t have a good role model to learn from.

They should not be used as a replacement for good parental modeling.

As the child grows older, peer influence begins to join parental influence: Older kids learn about self-regulation through observing and mimicking their peers.

However, the parent-adolescent relationship quality still plays a significant role in adolescents’ self-regulation.15

To help kids learn effective emotional control, parents can

- work to adopt better emotional regulation strategies themselves

- model positive emotions and adaptive emotion regulation for kids

- expose kids to a positive environment and people with good self-regulation

2. Parents Adopting a Responsive, Warm, and Accepting Parenting Style

Responsive, warm, and accepting parenting practices can help children with social-emotional development and behavioral control.

When parents are responsive, their children associate them with comfort and relief from stress.

Research shows that babies whose parents respond to their crying will stop crying at the sight or sound of the parent – they’re anticipating being picked up.

If the parent does not follow through with the expected comfort, the infant returns to the distressed state.16

Kids of responsive parents tend to have a broader range of regulatory skills.

Parents’ own belief in emotion management is also important.

Those who notice, accept, empathize with, and validate their children’s negative feelings tend to affect them positively.

They can teach kids emotional awareness by coaching them to verbalize how they feel and encourage them to problem-solve.

But if parents are dismissive or disapprove of emotional expressions, especially negative ones, children tend to develop destructive emotional regulation methods.17

These parents are usually uncomfortable expressing emotions and tend to coach the kids to suppress their feelings.

Parents who respond negatively or punish children for their emotions can cause them to get even more worked up, further activating their “fight-or-flight” nervous system and making it harder to calm down.18

When this happens, it may seem like the child is more defiant while their system is over-stimulated.

Telling a child amid a tantrum to “calm down” or threatening consequences may stimulate their systems to the point that they have a meltdown.

These children essentially have poorer self-regulation skills to calm a more worked-up system.

Punitive parenting practices are counterproductive in teaching emotional regulation.

Some parents take the sweeping-under-the-rug approach when it comes to negative emotions.

They feel that if you can’t see it, it doesn’t exist, or it will eventually go away.

Unfortunately, emotions don’t work that way.

Children whose parents dismiss emotions and do not talk about them in a supportive way are less able to manage their own emotions well.19

To effectively teach self-regulation to kids, parents can adopt the following parenting approach:

- be warm, accepting, and responsive to their child’s emotional needs

- talk about emotions

- accept, support, and show empathy to validate their negative feelings,

- be patient

- do not ignore, dismiss, discourage, punish, or react negatively to their child’s emotions, especially negative ones

3. Fostering a Positive Emotional Climate in the Family

The overall “climate” of the family is a good predictor of a child’s ability to self-regulate.20

Factors that affect emotional climate include the parents’ relationship, personalities, parenting style, parent-child relationships, sibling relationships, and the family’s beliefs about expressing feelings.

Kids feel accepted and secure when the emotional climate is positive, responsive, and consistent.

When the emotional climate is negative, coercive, or unpredictable, kids tend to be more reactive and insecure.

Parents who express positive emotions every day create a positive climate.

Parents who express excessive or constant negative emotions like sadness, anger, hostility, or criticism contribute to a negative situation and worse self-regulation in kids.

Marital conflict is one of the most common reasons for a negative family climate.

Kids from these families learn non-constructive ways to manage interpersonal conflicts and emotions. These kids are less likely to develop social competence.21

To create a positive family climate, parents can:

- express genuine positive emotions

- seek help to better handle marital conflicts or negative personalities within the family

- work on improving parent-child relationships and relationships among siblings

4. Grownups Teaching Self-Regulating Skills and Techniques

So far, we have discussed three ways parents can help their kids self-regulate.

If it looks like parents need to do more than the kids to regulate their emotions, you’re right.

Young children rely on adults to learn self-regulation.

As they age, school-age children’s executive functions will play a bigger role. 22

Parents can start teaching self-help techniques.

According to the process model of emotion regulation proposed by James Gross and colleagues, there are five stages in emotion generation.23

Different self-regulation strategies can be applied to the different stages to regulate individuals’ emotions.

Stage 1: Situation Selection – This refers to approaching or avoiding someone or some situations according to their likely emotional impact.

Stage 2: Situation Modification – Modifying the environment to alter its emotional impact.

Stage 3: Attentional Deployment – Redirecting attention within a given situation to influence their emotions.

Stage 4: Cognitive Change – Evaluating the situation to alter its emotional significance.

Stage 5: Response Modulation – Influencing emotional tendencies and reactions once they arise.

For children, most coping strategies tackle the latter three stages because they are less able to avoid or modify the environment.

They also tend not to understand the link between situation and emotion. 24

Here is a list of techniques parents can teach older children:

- Stage 3: Redirect attention (e.g., look, here is a red bunny!)

- Stage 4: Reappraisal by reframing the situation25 (e.g., we can turn this into a rocket )

- Stage 5: Coping skills (e.g., biofeedback26, count to 10, deep breathing and breathing exercises)m

5. Self-Care

For older children, especially adolescents and teenagers, self-care in everyday life is important in strengthening their internal resources to regulate emotions.

Activities that enhance self-care include:

- Exercise such as running, swimming, and other aerobic activity

- Mindfulness practice27 , such as meditation and yoga

- Adequate sleep and good sleep hygiene

- Relaxation treatments such as listening to music

Also See: 5 Tips on Developing Emotional Maturity

Final Thoughts on Emotional Regulation in Children

If the information on helping children develop self-regulation feels heavy, it is.

It is a reminder that our jobs as parents are paramount in shaping our children’s future.

However, we cannot provide a perfect home, genetics, or modeling.

Expecting perfection from ourselves may increase tension and negativity.

We need to keep working on our emotional muscles and strive to create a supportive environment.

And it’s never too late to start.

So take some deep breaths, accept yourself and your family for where you are, and dive in. It’s well worth the effort.

References

- 1.Parker JG, Asher SR. Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are low-accepted children at risk? Psychological Bulletin. Published online 1987:357-389. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.102.3.357

- 2.Perry DG, Kusel SJ, Perry LC. Victims of peer aggression. Developmental Psychology. Published online 1988:807-814. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.24.6.807

- 3.Graziano PA, Reavis RD, Keane SP, Calkins SD. The role of emotion regulation in children’s early academic success. Journal of School Psychology. Published online February 2007:3-19. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.002

- 4.Côté S, Morgan LM. A longitudinal analysis of the association between emotion regulation, job satisfaction, and intentions to quit. J Organiz Behav. Published online November 19, 2002:947-962. doi:10.1002/job.174

- 5.Buckholdt KE, Parra GR, Jobe-Shields L. Intergenerational Transmission of Emotion Dysregulation Through Parental Invalidation of Emotions: Implications for Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors. J Child Fam Stud. Published online June 25, 2013:324-332. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9768-4

- 6.Schore AN. Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self. 1st ed. Routledge; 2015.

- 7.McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Tibu F, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA III. Causal effects of the early caregiving environment on development of stress response systems in children. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Published online April 20, 2015:5637-5642. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423363112

- 8.Saarni C, Campos JJ, Camras LA, Witherington D. Emotional Development: Action, Communication, and Understanding. Handbook of Child Psychology. Published online June 1, 2007. doi:10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0305

- 9.Fox SE, Levitt P, Nelson III CA. How the Timing and Quality of Early Experiences Influence the Development of Brain Architecture. Child Development. Published online January 2010:28-40. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01380.x

- 10.Johnson JS, Newport EL. Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology. Published online January 1989:60-99. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(89)90003-0

- 11.boone tim, reilly anthony j., Sashkin M. SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY Albert Bandura Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1977. 247 pp., paperbound. Group & Organization Studies. Published online September 1977:384-385. doi:10.1177/105960117700200317

- 12.Carrère S, Bowie BH. Like Parent, Like Child: Parent and Child Emotion Dysregulation. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. Published online June 2012:e23-e30. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2011.12.008

- 13.Parke RD. Progress, Paradigms, and Unresolved Problems: A Commentary on Recent Advances in Our Understanding of Children’s Emotions. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1994;40(1):157-169.

- 14.Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL. Emotional Contagion. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. Published online June 1993:96-100. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770953

- 15.Farley JP, Kim-Spoon J. The development of adolescent self-regulation: Reviewing the role of parent, peer, friend, and romantic relationships. Journal of Adolescence. Published online June 2014:433-440. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.009

- 16.Tronick EZ. Emotions and emotional communication in infants. American Psychologist. Published online 1989:112-119. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.44.2.112

- 17.Lunkenheimer ES, Shields AM, Cortina KS. Parental Emotion Coaching and Dismissing in Family Interaction. Social Development. Published online May 2007:232-248. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00382.x

- 18.Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad T. Parental Socialization of Emotion. Psychol Inq. 1998;9(4):241-273. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16865170

- 19.Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad T. Parental Socialization of Emotion. Psychol Inq. 1998;9(4):241-273. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1

- 20.Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The Role of the Family Context in the Development of Emotion Regulation. Social Development. Published online May 2007:361-388. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x

- 21.Petrides KV, Sangareau Y, Furnham A, Frederickson N. Trait Emotional Intelligence and Children’s Peer Relations at School. Social Development. Published online August 2006:537-547. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006.00355.x

- 22.Rothbart MK, Sheese BE, Rueda MR, Posner MI. Developing Mechanisms of Self-Regulation in Early Life. Emotion Review. Published online April 2011:207-213. doi:10.1177/1754073910387943

- 23.Gross JJ. The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Review of General Psychology. Published online September 1998:271-299. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

- 24.Harris PL. Children’s understanding of the link between situation and emotion. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. Published online December 1983:490-509. doi:10.1016/0022-0965(83)90048-6

- 25.Goldin PR, McRae K, Ramel W, Gross JJ. The Neural Bases of Emotion Regulation: Reappraisal and Suppression of Negative Emotion. Biological Psychiatry. Published online March 2008:577-586. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.031

- 26.Davidson RJ, Schwartz GE. Patterns of Cerebral Lateralization During Cardiac Biofeedback versus the Self-Regulation of Emotion: Sex Differences. Psychophysiology. Published online January 1976:62-68. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1976.tb03339.x

- 27.Feldman G, Hayes A, Kumar S, Greeson J, Laurenceau JP. Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation: The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). J Psychopathol Behav Assess. Published online November 7, 2006:177-190. doi:10.1007/s10862-006-9035-8