Using words to appreciate a child reinforces their positive behavior and efforts, boosting their self-esteem and confidence. However, generic praise like “good job” does not convey sincere recognition of a child’s efforts.

Tailored and sincere appreciation helps foster a growth mindset in children, encouraging them to embrace challenges and continue developing their skills and capabilities.

Let’s explore the different ways to praise a child’s accomplishments without saying good job.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What are the words to appreciate a child?

- What are appreciation words for kindergarten students?

- Why is praise important to a child?

- How to appreciate a child for performance

- What are examples of direct and specific praise to give to a preschooler?

- What are effort praise examples?

- What are process praise examples?

- What is an encouraging note for a child from parents?

- What are kind words for kids?

- What are inspirational words for kids?

- What are praising words for students?

- What are nice things to say about a challenging child in your class?

- References

What are the words to appreciate a child?

Here are 20 words and phrases to appreciate a child.

- I appreciate your help.

- Thank you for helping.

- Your creativity amazes me.

- You have such a kind heart!

- I’m proud of your hard work.

- Your curiosity is inspiring.

- Keep being brave!

- You have unique ideas!

- You’re a fantastic friend!

- You are very kind!

- Your kindness warms my heart!

- You learn fast!

- Your energy is remarkable!

- You bring joy to people.

- You’re full of great surprises!

- You always try your best!

- You have a great sense of humor.

- What a positive attitude!

- You make a difference.

- Your smile brightens my day.

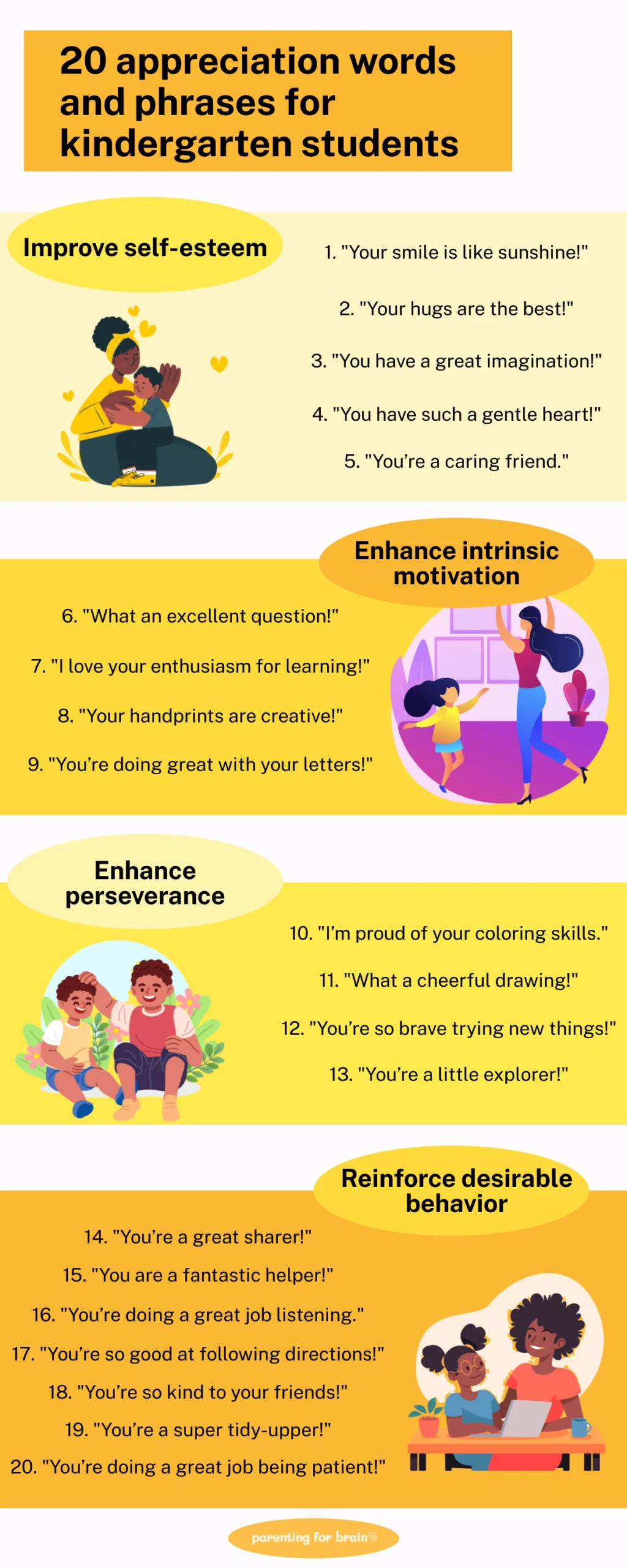

What are appreciation words for kindergarten students?

Here are 20 appreciation words and phrases for kindergarten students.

- Your smile is like sunshine!

- Your hugs are the best!

- You have a great imagination!

- You have such a gentle heart!

- You’re a caring friend.

- What an excellent question!

- I love your enthusiasm for learning!

- Your handprints are creative!

- You’re doing great with your letters!

- I’m proud of your coloring skills.

- What a cheerful drawing!

- You’re so brave trying new things!

- You’re a little explorer!

- You’re a great sharer!

- You are a fantastic helper!

- You’re doing a great job listening.

- You’re so good at following directions!

- You’re so kind to your friends!

- You’re a super tidy-upper!

- You’re doing a great job being patient!

Why is praise important to a child?

There are 3 reasons why praise is important to a child.1–3

- Improve children’s self-esteem: When used correctly, praise can benefit children with low self-esteem.

- Enhance intrinsic motivation: Positive words of encouragement can increase children’s intrinsic motivation to learn, according to a 2002 study published in the Psychological Bulletin.

- Enhance perseverance: Parents’ proper encouragement for kids can enhance children’s engagement and perseverance.

- Reinforce desirable behavior: A 2007 study at Lehigh University indicated that behavior-specific praise can increase and positively reinforce appropriate behavior in the classroom.

How to appreciate a child for performance

Research shows that nuances in how adults praise a child with words have significant consequences for children’s motivation and success in an activity. To appreciate a child for performance and motivate them, here are 7 tips on using words to appreciate. These 7 tips apply to complimenting someone’s child, too.

1. Praise sincerely and Honestly

Offer genuine and heartfelt praise to children. Compliments that don’t align with their self-perception or feel forced are often seen as insincere. Children are likely to disregard such praise, recognizing the lack of sincerity. For example, repeatedly saying ‘good job’ after every task can come across as routine and insincere.

| Don’t | Do |

|---|---|

| You’re a genius for solving that problem! (“Genius? I only got one out of three questions!”) | You came up with an excellent answer for the last question. |

| What an angel you are! (“I’m an angel for sharing a cookie? What about not doing homework last night?”) | It’s generous of you to share your cookie. |

| You did very well. I’m sure you will do well again next time. (manipulate) | I love the solution you came up with. |

2. Be specific and descriptive

Point out specific aspects of the child’s performance or describe what specific behavior has led to good results. Noticing small things signals you have paid attention and you care. A 2010 study conducted by Andrei Cimpian at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign showed that general praise lowered children’s motivation.4

| Don’t | Do |

|---|---|

| What an awesome painting! | I like the way you are using different colors on this drawing. |

| Great job! | You came up with a thoughtful answer and really nailed that question! |

3. Praise a child’s efforts and process, not their achievement or ability

Research shows how we attribute to events affects how we think of and respond to future events. Because effort is a quality that we all have the power to control and improve, children will, therefore, focus more on putting in the effort to practice or develop skills than on pursuing results alone.

Mastery encouragement helps children adopt a growth mindset and allows them to believe in practicing and improving skills. When facing failure, these children believe they have failed because they have not tried hard enough. Failure will be avoidable with more practice and hard work.

| Don’t | Do |

|---|---|

| What a smart boy! | I can see that you worked really hard on putting the pieces together. |

| Your ability in puzzle solving is excellent. | Your strategy in solving this puzzle by separating the colors was excellent! |

| You are such a great puzzle-solver! | You are good at trying different ways to solve a hard puzzle. |

4. Avoid controlling or conditional praise

A statement such as “I know you can do better” tries to motivate a child to try harder but signals control and manipulation. Conditional encouragements instill a sense of contingent self-worth in children.

When kids view their self-worth as contingent on approval and positive judgment, they seek goals that are easier to achieve and avoid activities that may cause negative judgment. Children become less creative, less self-directing, and more conforming.5

| Don’t | Do |

|---|---|

| I’m sure you will want to do better next time. | You’ve worked really hard on this every day and I like how you’ve drawn this picture using bright colors. |

| You did very well on that one, just as expected. | You did very well on that one. |

| If you keep it up every day, I believe you will do very well. | You did really well in collecting the data. |

5. Avoid comparison praise

Comparison praise leaves children vulnerable to future setbacks. Kids who are praised by comparison don’t stop comparing when they fail. Instead, they lose motivation faster.

| Don’t | Do |

|---|---|

| You are so good, just like your sister. | You are good at playing this game. |

| You are the smartest in your class! | You solved the problem with such great focus. |

6. Avoid easy-task praise or over-praise

Handing out encouraging words for tasks that are easy to complete or not done well is perceived as insincere. such praise can lower these children’s motivation and sense of self-worth in setbacks. A 2016 research review published in Child Development Perspectives revealed that inflated praise can backfire, lowering feelings of self-worth in children.6

7. Be spontaneous

Compliment unexpectedly and authentically. Don’t praise every little thing a child does to motivate them. The benefits of praising a child disappear when the compliment is expected.

What are examples of direct and specific praise to give to a preschooler?

Here are 20 examples of direct and specific praise to give to a preschooler and positively reinforce their behavior.

- You did a great job putting your toys away.

- I love how you used so many colors in your drawing.

- You were very patient waiting for your turn.

- You did an excellent job tying your shoes.

- I’m impressed with how you remembered the alphabet.

- Your building block tower is so creative.

- You solved the problem.

- You did a wonderful job washing your hands.

- You were very gentle with the classroom pet.

- I noticed you were really focused during story time.

- You did a great job counting to 10.

- Your manners at snack time were impeccable.

- You shared your crayons so nicely today.

- I love the way you helped your friend.

- You did a fantastic job during cleanup time.

- Your singing voice was beautiful in music time.

- I’m proud of you for trying new foods at lunch.

- You did such a good job lining up quietly.

- Your puzzle-solving skills are amazing.

- You were so brave during our fire drill.

What are effort praise examples?

Here are 20 effort praise examples.

- Your concentration on that puzzle was impressive.

- I can tell you put a lot of effort into your drawing.

- Your dedication to practicing is really paying off.

- It’s great to see how much you’ve improved.

- You really focused well during that game.

- I admire your persistence in solving that problem.

- You’ve shown impressive dedication to your science project.

- Your focus on your math homework is really commendable.

- The way you handle complex reading assignments is fantastic.

- Your continuous improvement in writing essays is evident.

- You’re showing great initiative in your group projects.

- Your persistence in studying for tests is paying off.

- You’re becoming quite skilled at problem-solving in math.

- You’ve been practicing a lot, and it shows.

- Your effort in learning to read is amazing.

- You’re demonstrating excellent research skills for your projects.

- The effort you put into learning new languages is fantastic.

- Your commitment to practicing your musical instrument is inspiring.

- Your creativity in art class is a result of your hard work.

- You’ve developed strong leadership skills in your team activities.

What are process praise examples?

Here are 20 process praise examples.

- You really thought through that math problem, well done!

- I can see how carefully you read that story, great job!

- Your attention to detail in your science experiment was excellent.

- I’m impressed by how you organized your ideas in that essay.

- The way you planned and executed your project shows great skill.

- You showed great patience and skill in learning that new piece on the piano.

- Your dedication to practicing your lines for the play is admirable.

- I noticed how you checked your work for errors, that’s a good habit.

- The strategies you used in that game were very clever.

- Your approach to solving conflicts with your peers is mature and thoughtful.

- You’ve really improved in presenting your ideas clearly in class discussions.

- The way you broke down that complex problem into smaller parts was excellent.

- You show a lot of creativity in finding different solutions to challenges.

- Your persistence in understanding challenging material is commendable.

- I appreciate how you always make sure to understand the instructions fully.

- Your ability to focus and not get distracted is improving wonderfully.

- The way you connect different ideas from various subjects is impressive.

- You’ve been really proactive in seeking help when you need it, that’s great.

- I admire how you manage your time and prioritize your tasks effectively.

- Your approach to peer collaboration and teamwork is very constructive.

What is an encouraging note for a child from parents?

An encouraging note for a child from parents is a short positive message that expresses support and praise to brighten a child’s day and remind them they are loved even when a parent is not physically present.

Here are 20 examples of encouraging notes for children from parents.

- Your determination in tackling that challenging homework really shows your strength of character.

- Every time you practice your violin, your improvement is evident, and it’s all because of your hard work.

- I noticed how you helped your sibling with their chores without being asked, your kindness is truly heartwarming.

- The creativity you put into your art projects brings out your unique personality, and it’s wonderful to see.

- You handled your disagreement with your friend very thoughtfully, showing great maturity.

- Your questions during our science museum visit were so insightful, it’s clear you’re really thinking deeply.

- Seeing you share your toys so willingly with your friends is a testament to your generous spirit.

- The patience you show when learning new things is a skill that will always help you succeed.

- Your excitement and willingness to learn new subjects in school makes us so proud.

- Watching you put so much effort into perfecting your handwriting has been inspiring.

- Your enthusiasm for reading and discovering new books is creating a fantastic adventure for your mind.

- Seeing the careful way you organize your schoolwork shows your growing responsibility.

- The respect you show your teachers and classmates makes a real difference in your classroom.

- Your ability to stay calm and collected during your soccer games shows true sportsmanship.

- The initiative you took to clean up the park with your friends was an outstanding act of community service.

- Your curiosity and the questions you ask during our nature walks make every trip a learning adventure.

- Noticing how you balance your studies and playtime is a sign of your growing time management skills.

- Watching you practice kindness, even when it’s difficult, is a true example of your strong character.

- Your joy and laughter when playing with your friends is contagious and brightens everyone’s day.

- These notes are crafted to encourage and validate the child’s efforts and processes, fostering a positive and growth-oriented mindset.

What are kind words for kids?

Kind words for kids are phrases or expressions that convey warmth, encouragement, support, and love, helping to boost their self-esteem and confidence. Here are 20 examples of kind words for kids.

- You are loved.

- I believe in you.

- Your ideas are wonderful.

- You make me proud every day.

- You are special and unique.

- Your kindness is a treasure.

- You have a big heart.

- Your creativity is amazing.

- You are important.

- I love your enthusiasm.

- You can achieve anything you set your mind to.

- You have a great sense of adventure.

- Your smile lights up the room.

- You are a great team player.

- Your questions show how smart you are.

- You are a joy to be around.

- I admire your bravery.

- You are a good listener.

- You make a difference.

- You are a star!

What are inspirational words for kids?

Here are 20 examples of inspirational words for kids.

- Every effort you make brings you one step closer to your goals.

- The way you care for your friends shows your big heart.

- Your excitement for learning new things is contagious.

- I love how you express your thoughts so clearly.

- Your determination to face challenges is inspiring.

- The imagination in your stories is truly captivating.

- You handle your mistakes with grace and learn from them.

- Your curiosity leads to such interesting discoveries.

- The respect you show others is a sign of your maturity.

- Your ability to find joy in small things is a wonderful trait.

- You have the power to make your dreams come true.

- Your creativity in solving problems is impressive.

- Every day, you grow stronger and more capable.

- Your laughter brings happiness to those around you.

- You show courage when trying things outside your comfort zone.

- The way you keep going, even when it’s tough, is admirable.

- You have a unique perspective that is valuable.

- Your kindness creates a ripple effect of goodness.

- Seeing you put in effort and improve is fantastic.

- Your presence makes the world a brighter place.

What are praising words for students?

Here are 20 examples of praising words for students.

- Your curiosity can lead to great discoveries, keep questioning.

- I see your potential to achieve great things.

- You have a unique way of looking at things that can be an asset.

- Your energy could be a powerful force when channeled positively.

- There’s a creative spark in you that is waiting to shine.

- You have the ability to be a strong leader.

- Your sense of humor can be a great tool for learning.

- I notice when you show moments of kindness.

- There’s a resilience in you that can help you overcome challenges.

- You have the power to make positive changes in your life.

- Your independence is a strength that can lead to success.

- When you do participate, it adds value to our class.

- You have a unique voice that deserves to be heard.

- Every day is a new opportunity for growth and change.

- You are capable of making more positive choices.

- Your moments of cooperation are appreciated and impactful.

- You bring a different perspective that can be valuable.

- I believe in your ability to improve and succeed.

- Your journey is unique and important.

- Remember, it’s never too late to turn things around.

What are nice things to say about a challenging child in your class?

Here are 20 nice things to say about a challenging child in your class.

- Your efforts to stay focused today were noticeable and appreciated.

- You handled today’s lesson better than before, and that’s a great sign of progress.

- I can see you’re trying, and that’s what really matters.

- Your questions today showed you’re starting to engage more, which is fantastic.

- The way you helped tidy up shows your responsible side.

- You have a lot of potential in science, and I’m here to help you unlock it.

- When you do speak up, your ideas are really interesting.

- Your attendance has improved, and that’s great.

- I see moments when you’re really thinking about the material.

- Your doodles are creative; maybe we can channel that creativity into your projects.

- You stayed calmer today during the discussion, and that’s a big improvement.

- There’s a spark of curiosity in you; let’s kindle that into a flame.

- When you do focus, you show a lot of understanding.

- You’re starting to make better choices, and that’s important.

- The effort you put into today’s class didn’t go unnoticed.

- Even though it’s hard, you keep coming to class, and that’s commendable.

- You have unique skills that we haven’t fully discovered yet.

- Your perspective on today’s topic was unique and valuable.

- I know you have great potential. I believe in you.

- You have the ability to turn things around, and I believe you will.

References

- 1.Kern L, Clemens NH. Antecedent strategies to promote appropriate classroom behavior. Psychology in the Schools. Published online December 13, 2006:65-75. doi:10.1002/pits.20206

- 2.Smith RE, Smoll FL. Self-esteem and children’s reactions to youth sport coaching behaviors: A field study of self-enhancement processes. Developmental Psychology. Published online November 1990:987-993. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.26.6.987

- 3.Henderlong J, Lepper MR. The effects of praise on children’s intrinsic motivation: A review and synthesis. Psychological Bulletin. Published online 2002:774-795. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.774

- 4.Cimpian A. The impact of generic language about ability on children’s achievement motivation. Developmental Psychology. Published online 2010:1333-1340. doi:10.1037/a0019665

- 5.Crocker J, Knight KM. Contingencies of Self-Worth. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. Published online August 2005:200-203. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00364.x

- 6.Brummelman E, Crocker J, Bushman BJ. The Praise Paradox: When and Why Praise Backfires in Children With Low Self‐Esteem. Child Dev Perspectives. Published online March 3, 2016:111-115. doi:10.1111/cdep.12171