Classical conditioning, a foundational concept introduced by Ivan Pavlov through his work with dogs, explains how associative learning occurs by pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus to elicit a conditioned response. This learning mechanism demonstrates how organisms, including humans, respond to previously neutral stimuli with conditioned reactions, mirroring natural responses to stimuli that inherently trigger such reactions.

The principles of classical conditioning are evident in various aspects of daily life, from emotional reactions to specific environments to the development of phobias and preferences, illustrating this learning theory’s broad applicability and impact.

Classical conditioning encompasses several phases: before acquisition, acquisition, and after acquisition, with effectiveness depending on the timing and nature of stimulus pairing. Delay conditioning is the most effective form, while backward conditioning is the least. This learning process also includes first-order, second-order, and higher-order conditioning, illustrating the layered complexity of associative learning.

Stimulus generalization and discrimination are critical in classical conditioning, affecting how organisms respond to similar or distinct stimuli. Fear conditioning, a type of classical conditioning, is pivotal in understanding phobias, anxiety, PTSD, and OCD, linking neutral stimuli with adverse experiences.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What is classical conditioning?

- Who discovered classical conditioning?

- What are classical conditioning examples in everyday life?

- 1. A warm and nurturing teacher motivates students

- 2. A harsh and strict teacher demotivates students

- 3. Fear of painful medical procedure

- 4. Food aversion

- 5. Anxiety over needles

- 6. Stage fright

- 7. Coffee in the morning

- 8. Storm anxiety in pets

- 9. Praises encourage a child to feel happy about their good behavior

- 10. A parent turns homework into misery

- 11. A parent turns homework into a game

- 12. Anxious about exams

- 13. Getting A’s in exams

- 14. Crave for hotdogs

- 15. Parents’ angry expressions

- 16. Advertising

- 17. Cellphone ringtone

- 18. Bread-baking aroma

- 19. Festive music

- 20. Dog-walking

- What are examples of classical conditioning in the classroom?

- What are examples of classical conditioning in parenting?

- What are examples of classical conditioning in relationships?

- What are unethical classical conditioning examples?

- What is an unconditioned stimulus?

- What is an unconditioned response?

- What is a neutral stimulus?

- What is a conditioned stimulus?

- What is a conditioned response?

- What are the three phases of classical conditioning?

- How long does it take for classical conditioning to work?

- What is forward conditioning?

- What is backward conditioning?

- Which classical conditioning is the most effective?

- What is Second-order conditioning?

- What is fear conditioning?

- What is extinction in classical conditioning?

- Can you reverse classical conditioning?

- What is an extinction burst?

- What is spontaneous recovery?

- Is classical conditioning manipulative?

- Is classical conditioning good or bad?

- What are the 2 types of associative learning?

- References

What is classical conditioning?

Classical conditioning, also known as Pavlovian conditioning or respondent conditioning, is learning through the pairing of a neutral conditioned stimulus (CS) with an unconditioned stimulus (US) to produce a conditioned response (CR), which is the same as the unconditioned response (UR). It is associative learning, where one learns that a preceding stimulus signals a subsequent event and, therefore, triggers a conditioned response.

What is Pavlov’s dog?

Pavlov’s dog refers to the subject of a series of experiments conducted by Pavlov in the early 20th century, pivotal in establishing the principles of classical conditioning. In the experiments, Pavlov introduced a neutral stimulus, such as a bell sound or metronome, which initially did not affect the salivation of the dogs.

After ringing the bell, food was offered to the dogs. Once the bell sounds were paired with food several times, the dogs started salivating even without seeing food. The dogs are then classically conditioned to salivate at the sound of the bell.

Who discovered classical conditioning?

Ivan Pavlov (Ivan Petrovich Pavlov), a Russian neurologist and physiologist, discovered classical conditioning while investigating the digestive system in dogs in the early 1900s. Pavlov observed that his dogs would salivate every time he entered the room, whether or not he brought food, because the dogs had associated his entrance into the room with being fed.1,2

What are classical conditioning examples in everyday life?

Here are 20 examples of Ivan Pavlov’s classical conditioning in everyday life.

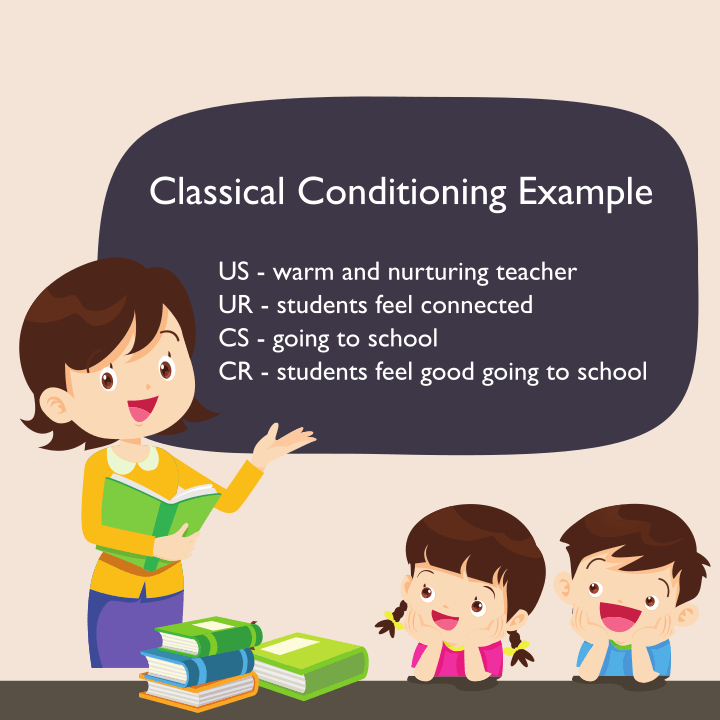

1. A warm and nurturing teacher motivates students

A warm and nurturing teacher (US) makes students feel connected (UR).

Students associate going to school (CS) with the teacher.

Going to school makes students feel connected (CR).

2. A harsh and strict teacher demotivates students

A harsh and strict teacher (US) makes students feel bad (UR).

Students associate going to school (CS) with the harsh teacher.

Going to school makes students feel bad (CR).

3. Fear of painful medical procedure

A child experiences a painful medical procedure in a hospital (US), which is distressing (UR).

The child then associates the hospital environment (CS) with this distress.

Visiting a hospital makes the child feel anxious or fearful (CR).

4. Food aversion

A person eats contaminated food (US), gets sick, and feels awful (UR).

The person associates the sight of food (CS) with contaminated food.

The sight of food makes the person feel awful (CR).

5. Anxiety over needles

Getting a flu shot (US) hurts and makes a child cry (UR).

The child associates the needle (CS) with getting hurt.

The sight of the needle makes the child cry (CR).

6. Stage fright

Being laughed at (US) in a presentation makes a person feel nervous (UR).

The person associates giving a presentation (CS) with being laughed at.

Giving a presentation makes the person feel nervous (CR).

7. Coffee in the morning

Drinking coffee (US) increases alertness (UR).

A coffee drinker associates the aroma of coffee brewing with drinking coffee.

Smelling coffee makes a coffee drinker feel alert (CR).

8. Storm anxiety in pets

Loud thunderstorms (US) accompanied by changes in air pressure scare (UR) pets.

Animals associate changes in air pressure with thunderstorms.

When there is a change in air pressure preceding a storm, animals become anxious.

9. Praises encourage a child to feel happy about their good behavior

Being praised for good behavior (US) makes a child feel proud (UR).

The child associates the behavior (CS) with the praise.

Engaging in good behavior makes the child feel proud (CR).

10. A parent turns homework into misery

A parent yells at their kid (US) for not doing homework, making the child feel miserable (UR).

The child associates homework (CS) with yelling.

Doing homework makes the child feel miserable (CR).

11. A parent turns homework into a game

Turning homework into a game (US) makes a child happy (UR).

The child associates homework (CS) with playing games.

Doing homework makes the child feel happy (CR).

12. Anxious about exams

Being punished (US) by their parents for failing an exam feels bad (UR).

The child associates exams (CS) with punishment.

Exams make the child feel bad (CR).

13. Getting A’s in exams

Being rewarded (US) for good grades in an exam makes a child feel happy (UR).

The child associates exams (CS) with rewards.

Exams make the child feel happy (CR).

14. Crave for hotdogs

Whenever Dad spends time (US) with his son, he buys him a hotdog, and the son enjoys time together (UR).

The son associates hotdogs with spending time together.

Eating a hotdog makes the child feel happy (CR), as if he’s spending time with his Dad.

15. Parents’ angry expressions

A parent yells (US) with angry facial expressions, and the child is scared (UR).

The child associates angry expressions (CS) with yelling.

Seeing angry expressions on the parent’s face makes the child feel scared (CR).

16. Advertising

Kids playing together (US) with a toy in commercials makes a child feel connected and happy (UR).

A child associated the toy (CS) with kids playing together.

Owning the toy makes the child feel connected and happy (CR).

17. Cellphone ringtone

Whenever a friend calls (US), he makes a person feel good (UR).

The person associated the special ringtone (CS) for this friend with the friend’s calling.

Hearing the ringtone from any phone makes this person feel good (CR).

18. Bread-baking aroma

Mothers baking bread at home (US) create happy childhood memories (UR).

Children learn to associate the smell of baking bread (CS) with these happy times.

The scent of baking bread as adults evokes feelings of happiness and nostalgia (CR).

19. Festive music

The holiday season, characterized by joy, music, and festivity (US), creates happy memories (UR).

Department stores play holiday music during the shopping season (CS).

This music rekindles the festive spirit, promoting joy and generosity (CR).

20. Dog-walking

Walking with its owner (US) excites a dog (UR).

The dog links its owner’s actions, like getting ready (CS), with walks.

These actions alone trigger the dog’s excitement (CR).

What are examples of classical conditioning in the classroom?

Here are 2 examples of classical conditioning in the classroom.

Subject-teacher association

A subject teacher is mean (US), and the students don’t like him (UR).

Students associate the subject (CS) with the teacher.

Students don’t like the subject or study for it (CR).

Behavior management chart

Students are rewarded with a toy (US) that the students like (UR) when they demonstrate good behavior.

Students associate good behavior (CS) with the toy.

Students like showing good behavior (CR).

What are examples of classical conditioning in parenting?

Here are 3 examples of classical conditioning in parenting.

Calming voice

When a child falls and scrapes her knee, a parent uses a calm voice while putting on a bandaid (US) to alleviate the pain, and the child feels soothed and comforted (UR).

The sound of the calm voice (CS) is associated with comfort.

The child feels calm and secure (CR) hearing her parent’s gentle voice.

Happy teeth brushing

Each time a child brushes their teeth without being asked, they get a sticker (US), which they find exciting (UR).

Teeth brushing (CS) becomes associated with getting a sticker.

The child feels excited and proud (CR) about brushing their teeth autonomously.

Being polite

After a child says “please” or “thank you,” a parent smiles broadly (US), making the child feel acknowledged and happy (UR).

Saying “please” or “thank you” (CS) becomes linked with receiving a happy response.

The child feels positive and encouraged (CR) to use polite words.

What are examples of classical conditioning in relationships?

Here are 4 examples of classical conditioning in relationships.

Favorite dating cafe

A couple frequently shares affectionate moments at a particular cafe (US), leading to feelings of happiness (UR) in that setting.

The couple associates the cafe (CS) with happiness.

The couple feels happy (CR) just by visiting or thinking about the cafe.

Stressful tone of voice

A specific tone of voice is used by a partner during arguments (US), which usually leads to feelings of anxiety (UR).

The person associates the tone of voice (CS) with anxiety.

Hearing this tone alone, regardless of context, causes anxiety (CR).

Hugs are love

A couple hugs (US) to show affection and love (UR).

These gestures (CS) become linked to feeling loved.

Hugging elicits a sense of romance and love (CR).

Happiness gifts

Receiving gifts during positive interactions (US) leads to feelings of happiness (UR).

The act of receiving gifts (CS) becomes linked to happiness.

Receiving or giving gifts evokes feelings of happiness (CR).

What are unethical classical conditioning examples?

Here are two unethical examples of classical conditioning in real life.

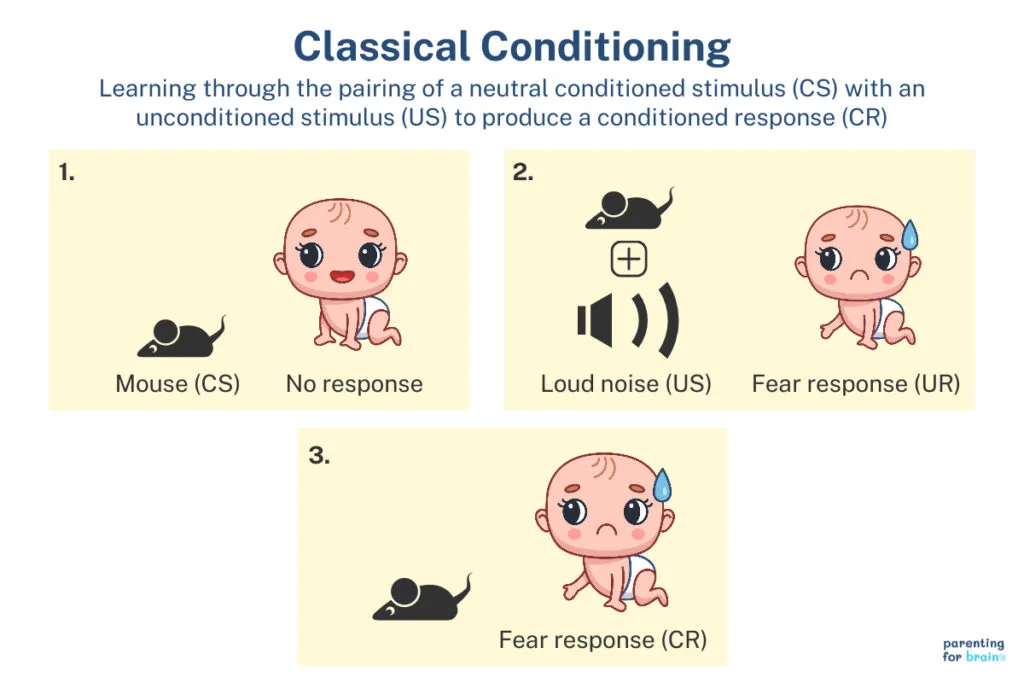

Fear conditioning in the Little Albert experiment

American psychologist John B. Watson set out to develop a therapy for phobias. In the experiment, Watson conditioned Little Albert, a young child, to fear a rat by pairing the sight of the rat (conditioned stimulus) with a loud, frightening noise (unconditioned stimulus).

After several pairings, Albert began to fear the rat even without the noise. This fear conditioning experiment is considered unethical by modern standards due to the deliberate infliction of psychological distress on a child without consent or ethical oversight.1

Affective conditioning in children

Food advertising uses affective or evaluative conditioning to influence children’s eating habits by associating food products, especially unhealthy ones, with positive and appealing stimuli, such as animated characters, bright colors, or fun scenes in a commercial. Systematic research reviews have found that children’s exposure to food cues in advertising is related to increased choice and intake of foods, particularly for snack foods.3

This pairing creates a conditioned response in children and influences their food choices and intake. Children develop cravings for these foods, contributing to unhealthy eating behaviors.

What is an unconditioned stimulus?

An unconditioned stimulus (US) in classical conditioning is a stimulus that naturally and automatically triggers an unconditioned response (UR) without prior learning. An unconditioned stimulus, therefore, is a biologically potent stimulus that can elicit an involuntary response. This stimulus-response relationship is innate, meaning the response is a reflexive or biological reaction that occurs naturally when the unconditioned stimulus is presented.

For example, food was the unconditioned stimulus that naturally and automatically triggered the dog’s salivation in Pavlov’s experiments.

What is a primary reinforcer?

A primary reinforcer is a stimulus that naturally satisfies a basic biological need or desire, such as food, water, or warmth, without prior learning. In classical conditioning, a primary reinforcer is an unconditioned stimulus that can naturally generate an unconditioned response. If a primary reinforcer is repeatedly paired with a neutral stimulus, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus capable of eliciting the same response as the primary reinforcer.4

For example, sleep is a primary reinforcer that can satisfy a person’s biological need for rest. If a child goes to bed early, sleep produces resting and reinforces going to bed early.

What is an unconditioned response?

An unconditioned response (UR) is an automatic, innate reaction elicited by an unconditioned stimulus without prior learning or conditioning. This response is reflexive and occurs naturally when the unconditioned stimulus is presented.

For example, the dog’s initial salivation was an unconditioned response to food, the unconditioned stimulus and primary reinforcer in Pavlov’s experiments.

What is a neutral stimulus?

A neutral stimulus (NS) in classical conditioning is an initially irrelevant stimulus that does not naturally elicit a response of interest. Before conditioning, a neutral stimulus does not produce a reflexive response. The neutral stimulus gradually acquires the capacity to trigger a similar response and becomes a conditioned stimulus after being consistently paired with the unconditioned stimulus.

For example, the sound of a bell or metronome was a neutral stimulus that initially did not elicit salivation in the dogs in Pavlov’s experiments.

What is a conditioned stimulus?

A conditioned stimulus (CS) is a previously neutral stimulus that begins to elicit a learned or conditioned response after being repeatedly paired with an unconditioned stimulus. The process that transforms a neutral stimulus into a conditioned stimulus is classical conditioning.

For example, in Pavlov’s experiments, the sound of a bell or metronome became a conditioned stimulus that could elicit salivation in dogs after being repeatedly paired with food.

What is a conditioned response?

A conditioned response (CR) is a learned reaction to a previously neutral stimulus that has become a conditioned stimulus through classical conditioning.

For example, the dog’s salivation on hearing the bell sound alone was a conditioned response in Pavlov’s experiments.

What are the three phases of classical conditioning?

The three phases of classical conditioning are before acquisition, acquisition, and after acquisition.

- Before acquisition: Before classical conditioning begins, the unconditioned stimulus (US) naturally produces an unconditioned response (UR). The neutral stimulus (NS) does not trigger a response.

- Acquisition: During acquisition, the neutral stimulus is paired repeatedly with the unconditioned stimulus to form an association.

- After acquisition: The neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS) that can trigger the same response as the unconditioned stimulus, even when not present.

How long does it take for classical conditioning to work?

Classical conditioning can occur rapidly, sometimes in just one pairing or within a second, especially in scenarios like fear conditioning. On the other hand, it can also be a prolonged process, requiring hundreds of pairings or even years, as observed in acquiring a new language. How long it takes for classical conditioning to work varies, depending on context and the type of pairing.

What is forward conditioning?

Forward conditioning is classical conditioning with a special temporal relationship, where the conditioned stimulus is presented before the unconditioned stimulus to form an association.

What are the 3 types of forward classical conditioning?

The 3 types of forward classical conditioning are delay, trace, and simultaneous.

- Delay conditioning: CS is followed immediately by the US.

- Trace conditioning: CS is followed by a time gap and then the US.

- Simultaneous conditioning: CS and US show up and disappear simultaneously.

What is backward conditioning?

Backward conditioning is classical conditioning, where the conditioned stimulus comes after the unconditioned stimulus ends. Whether backward conditioning can create conditional learning is debated by researchers.

Research indicates that the frequency of pairings affects learning outcomes. When pairings are few (after 10 pairings), the conditioned stimulus emerges as a predictor of the unconditioned stimulus, demonstrating excitatory potential. However, with an increased number of pairings (after 160 pairings), the CS starts to signal the absence of the US, indicating inhibitory characteristics. This shift highlights how the quantity of CS-US pairings can alter their associative learning dynamics.5

Which classical conditioning is the most effective?

Delay conditioning is the most effective type of classical conditioning in most situations, followed by trace conditioning. Compared to trace conditioning, associative learning is usually more robust and faster when delay conditioning is used. As the gap in trace conditioning is lengthened, it becomes harder to form an association.6

Which classical conditioning is the least effective?

Backward conditioning is the least effective conditioning in most situations. Research shows that backward conditioning doesn’t work in many conditions.7

What is first-order conditioning?

First-order conditioning is regular conditioning, in which a neutral stimulus is paired with an unconditioned stimulus to become a conditioned stimulus.

What is Second-order conditioning?

Second-order conditioning is a process in which a previously conditioned stimulus is used to condition a new stimulus, creating a second layer of conditioning.8

What is higher-order conditioning?

Higher-order conditioning extends classical conditioning by creating associations beyond the basic conditioned-unconditioned stimulus pairing. It involves linking a new neutral stimulus with an already established conditioned stimulus, leading to the neutral stimulus eliciting the conditioned response without direct association with the unconditioned stimulus.

Higher-order conditioning is any conditioning beyond the first-order conditioning. It helps explain complex learning and behavior patterns, where responses are formed to direct experiences and a network of associated cues.9

For example, if a child learns to associate a bell sound (first-order conditioned stimulus) with receiving a treat (unconditioned stimulus), and then light (new neutral stimulus) is repeatedly presented with the bell sound, the child may start to respond to the light as if it predicts the treat. The light becomes a second-order conditioned stimulus. This process can continue, with additional stimuli becoming conditioned similarly (third-order conditioning, and so on), forming a chain of learned associations.

What is stimulus generalization?

Stimulus generalization occurs when a response to a specific stimulus is elicited by similar, but not identical, stimuli. This happens because the subject perceives these similar stimuli as being close enough to the original conditioned stimulus.

For example, in the Little Albert experiment, the baby’s fear of the white rat wasn’t limited to only white rats. The baby also became scared of other small animals, such as white rabbits or dogs. The poor child also feared soft white objects such as white cotton balls.

What is stimulus discrimination?

Stimulus discrimination is the ability to differentiate between similar stimuli and respond only to a specific conditioned stimulus. This occurs when a subject learns that only the original stimulus predicts the unconditioned stimulus, while similar stimuli do not. Stimulus discrimination is the opposite of generalization.

For example, if a child has been conditioned to expect a reward after hearing a specific bell tone, the child will learn to respond only to that particular tone but not to others.10

What is fear conditioning?

Fear conditioning is a type of classical conditioning where an individual learns to associate a neutral stimulus with a frightening or unpleasant event, leading to the expression of fear responses to that previously neutral stimulus.

For example, if a child hears a specific sound (neutral stimulus) right before experiencing something scary (unconditioned stimulus), they may start to feel anxious or fearful just from hearing that sound in the future, even in the absence of the scary event.

Is the fear of dogs classical conditioning?

Yes, the fear of dogs is often the result of classical conditioning. This occurs when a neutral stimulus (dogs) becomes associated with a frightening experience (like being bitten or chased by a dog).

After this association is formed, the sight or presence of dogs alone can trigger fear or anxiety, even if the dog is not threatening. This learned fear response is a classic example of how classical conditioning operates in real-life situations.

Yes, anxiety is related to classical conditioning as a neutral stimulus (like a place or situation) becomes associated with an anxiety-provoking event (like a panic attack or a stressful situation). Over time, the previously neutral stimulus alone can trigger an anxiety response. This process is often seen in phobias and other anxiety disorders.

How does trauma relate to classical conditioning?

Trauma is related to classical conditioning when a traumatic event (US) leads to a strong emotional response (UR). Subsequently, neutral stimuli during the trauma can become conditioned stimuli (CS), triggering the same emotional response (CR).

This process is often observed in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), where reminders of the traumatic event evoke intense emotional reactions.

Yes, PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder, is related to classical conditioning as it involves associative fear learning. This learning is acquired during the traumatic event, with neutral stimuli that appear in the traumatic environment gaining the capacity to trigger anxiety. PTSD symptoms, such as re-experiencing and avoidance, are then activated by conditioned stimuli despite their safety.11

Yes, OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder, is related to classical conditioning as it forms the initial associations between neutral stimuli and anxiety-producing events.

For example, touching a doorknob (neutral stimulus) becomes linked with the fear of contamination (unconditioned stimulus), leading to anxiety (unconditioned response). Over time, the doorknob alone (now a conditioned stimulus) triggers anxiety (conditioned response), even in the absence of actual contamination. This process can lead to the development of obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors as individuals try to avoid or neutralize these classically conditioned fear responses.12

Can classical conditioning cause mental health issues?

Classical conditioning can contribute to the development of mental health issues, particularly those involving phobias, anxiety disorders, PTSD, and OCD. However, classical conditioning is just one factor among many in the complex development of mental health disorders. Genetics, environment, life experiences, and individual psychological factors also play significant roles.

What is extinction in classical conditioning?

Extinction in classical conditioning refers to the gradual weakening and eventual disappearance of a conditioned response. This happens when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus initially eliciting the response. Over time, the conditioned behavior decreases and stops, indicating that extinction has occurred.

For example, after the bell sound is repeatedly paired with no food, the dog’s salivation eventually stops hearing the sound.13

Can you reverse classical conditioning?

Yes, you can counter the effects of classical conditioning through a process called counterconditioning. Studies show that in counterconditioning, behavior is modified through a new association with a stimulus of an opposite valence to the original stimulus.14

What is counterconditioning?

Counterconditioning is a form of classical conditioning. It is a behavioral therapy technique that involves re-associating a stimulus that elicits an unwanted response with a new one incompatible with the unwanted one.15

This process is typically achieved by repeatedly pairing the stimulus with a positive or relaxing experience, leading to a change in the individual’s response to the stimulus. Counterconditioning is commonly used in treating phobias and anxiety disorders to reduce fear or anxiety by creating a new, positive associative learning.

For example, a person fearful of dogs is repeatedly exposed to dogs while doing something enjoyable. Gradually, their fear response is replaced with positive feelings.

What is the difference between counterconditioning and extinction?

The main difference between counterconditioning and extinction is their approaches to modifying learned behaviors. Counterconditioning involves replacing an undesirable response with a desirable one, while extinction focuses on weakening a conditioned response. Thus, counterconditioning seeks to learn a new behavior to replace the old one, while extinction aims to break the association that caused it.

Which is better: extinction or counterconditioning?

Some studies have found that counterconditioning is more effective than extinction in reducing cue-induced craving and learned fear.16,17

What is an extinction burst?

An extinction burst temporarily increases the conditioned response’s frequency, intensity, or duration when the unconditioned stimulus is first removed. When the expected conditioned response stops following a previously conditioned stimulus, the individual initially responds with an increased level of conditioned behavior to bring back the unconditioned response.

For example, if a child has learned to receive attention (conditioned response) by whining (conditioned stimulus) and the parent suddenly stops responding to the whining, the child may initially whine more loudly or frequently to regain the lost attention.

What is spontaneous recovery?

Spontaneous recovery is when a previously extinguished conditioned response reappears after some time without exposure to the conditioned stimulus. This sudden return of a previously extinct behavior is usually temporary and weaker than the original conditioned response.

For example, a child who once got frightened by a loud thunderstorm has learned to stop reacting fearfully to the sound of thunder, indicating the extinction of the conditioned fear response. However, after a long period without storms, a sudden, loud clap of thunder might unexpectedly trigger a brief return of the fear response, even though the child had seemingly overcome this fear.

Is classical conditioning manipulative?

Yes, classical conditioning can be used to manipulate behavior in situations such as advertising, political campaigns, and classroom management through evaluative conditioning. Evaluative conditioning is a form of classical conditioning that involves intentionally changing the perception of a stimulus by associating it with another stimulus that elicits a particular reaction.

For example, products are often associated with positive emotions or desirable outcomes in advertising, leading consumers to develop a favorable attitude toward the product.

How do you break bad habits with classical conditioning?

To break bad habits with classical conditioning, here are 3 strategies.

- Altering the situation or stimuli: Prevent automatic activation of the habit’s script. For example, If someone has a habit of snacking on unhealthy food while watching TV, they could alter this situation by keeping healthy snacks like fruits or vegetables within easy reach instead of chips or sweets.

- Providing clear and direct information: Present the negative long-term outcomes of the habit and the positive outcomes of alternative behaviors. For example, educating a person about the long-term negative effects of smoking, such as increased risk for lung cancer and heart disease, along with highlighting the positive outcomes of quitting, like improved lung function and reduced risk of chronic diseases.

- Ensuring alternative behaviors offer short-term positive outcomes: Increase the likelihood of a new habit emerging. For example, replacing coffee with herbal tea or a healthy smoothie can provide immediate positive outcomes for someone trying to quit caffeine.

Is classical conditioning good or bad?

Classical conditioning is both good and bad. On the beneficial side, psychologists believe that human conditioning is the most straightforward and unconscious learning method.18

This process is automatic and helps us adapt to various environments. Classical conditioning helps us recognize and respond to potential dangers, enhancing our survival. However, it also contributes to the development of irrational fears or phobias, where a harmless object or situation triggers a fear response due to previous associations.

Therefore, classical conditioning can be both good and bad; it’s a powerful learning tool with positive and negative outcomes depending on the context and the associations formed.

What are the 2 types of associative learning?

The 2 types of associative learning are classical conditioning and operant conditioning. Operant conditioning is a learning process where the likelihood of a behavior is modified by its consequences. In this process, behaviors followed by positive outcomes tend to be repeated, while those followed by adverse outcomes are less likely to occur.

Operant conditioning involves reinforcement, which increases behavior frequency, and punishment, which decreases behavior frequency. Reinforcement can be positive (adding a desirable stimulus) or negative (removing an undesirable one). Similarly, punishment can involve adding an unpleasant stimulus or removing a pleasant one. This form of conditioning emphasizes the role of consequence in shaping behavior.

What is the difference between classical and operant conditioning?

The main difference between classical and operant conditioning is that classical conditioning associates involuntary behavior with a stimulus, whereas operant conditioning associates voluntary action with a consequence.

Classical conditioning, discovered by Ivan Pavlov, involves learning by associating a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus, leading to a conditioned response. Operant conditioning, developed from Thorndike’s Law of Effect and expanded by B.F. Skinner involves learning to increase or decrease voluntary behaviors using reinforcement or punishment.

Both are forms of associative learning but differ in their focus on involuntary versus voluntary behaviors and the role of stimuli versus consequences.

References

- 1.Ploog BO. Classical Conditioning. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. Published online 2012:484-491. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-375000-6.00090-2

- 2.Clark RE. The classical origins of Pavlov’s conditioning. Integr psych behav. Published online October 2004:279-294. doi:10.1007/bf02734167

- 3.Folkvord F, Anschütz DJ, Boyland E, Kelly B, Buijzen M. Food advertising and eating behavior in children. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. Published online June 2016:26-31. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.11.016

- 4.Delgado MR, Jou RL, Phelps EA. Neural Systems Underlying Aversive Conditioning in Humans with Primary and Secondary Reinforcers. Front Neurosci. Published online 2011. doi:10.3389/fnins.2011.00071

- 5.Chang RC, Blaisdell AP, Miller RR. Backward conditioning: Mediation by the context. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. Published online 2003:171-183. doi:10.1037/0097-7403.29.3.171

- 6.BALSAM P. Relative Time in Trace Conditioning. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Published online May 1984:211-227. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb23432.x

- 7.McSweeney FK, Bierley C. Recent Developments in Classical Conditioning. J CONSUM RES. Published online September 1984:619. doi:10.1086/208999

- 8.Hussaini SA, Komischke B, Menzel R, Lachnit H. Forward and backward second-order Pavlovian conditioning in honeybees. Learn Mem. Published online October 2007:678-683. doi:10.1101/lm.471307

- 9.Gewirtz JC, Davis M. Using Pavlovian Higher-Order Conditioning Paradigms to Investigate the Neural Substrates of Emotional Learning and Memory. Learn Mem. Published online September 1, 2000:257-266. doi:10.1101/lm.35200

- 10.Dunsmoor JE, Paz R. Fear Generalization and Anxiety: Behavioral and Neural Mechanisms. Biological Psychiatry. Published online September 2015:336-343. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.010

- 11.Lissek S, van Meurs B. Learning models of PTSD: Theoretical accounts and psychobiological evidence. International Journal of Psychophysiology. Published online December 2015:594-605. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2014.11.006

- 12.Markarian Y, Larson MJ, Aldea MA, et al. Multiple pathways to functional impairment in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. Published online February 2010:78-88. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.09.005

- 13.Likhtik E, Paz R. Amygdala–prefrontal interactions in (mal)adaptive learning. Trends in Neurosciences. Published online March 2015:158-166. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2014.12.007

- 14.Keller NE, Hennings AC, Dunsmoor JE. Behavioral and neural processes in counterconditioning: Past and future directions. Behaviour Research and Therapy. Published online February 2020:103532. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2019.103532

- 15.de Jong PJ, Vorage I, van den Hout MA. Counterconditioning in the treatment of spider phobia: effects on disgust, fear and valence. Behaviour Research and Therapy. Published online November 2000:1055-1069. doi:10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00135-7

- 16.Van Gucht D, Baeyens F, Vansteenwegen D, Hermans D, Beckers T. Counterconditioning reduces cue-induced craving and actual cue-elicited consumption. Emotion. Published online 2010:688-695. doi:10.1037/a0019463

- 17.Newall C, Watson T, Grant KA, Richardson R. The relative effectiveness of extinction and counter-conditioning in diminishing children’s fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy. Published online August 2017:42-49. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.006

- 18.Rehman I, Mahabadi N, Sanvictores T, Rehman C. statpearls. Published online August 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470326/